The week of December 2 – 8 takes us from Day 6 to Day 11. This week we will highlight the craters Linné and Cassini, viewable on Tuesday evening.

The week of December 2 – 8 takes us from Day 6 to Day 11. This week we will highlight the craters Linné and Cassini, viewable on Tuesday evening.

Linné: [NE/G11] Linné is a simple, relatively young crater with an interesting history. It is 1.5 miles in diameter (only about 1.3 arc-seconds at the average distance of the Moon), which makes it about twice the size of Meteor Crater in Arizona. Linné is surrounded by very light-colored material, and because its appearance changes so much with different angles of illumination this was once taken as evidence that the Moon was not a totally dead place. In 1866 it was erroneously reported that Linné had vanished. The idea caught on and was cited as proof that the Moon was still geologically active. Observe Linné under different lighting angles and see if you can convince yourself (if you didn’t know better) that Linné could disappear.

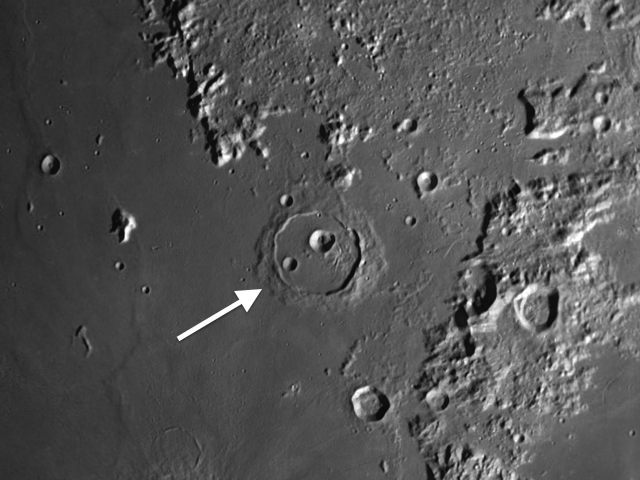

Cassini: [NE/E10] Can you tell by looking at Cassini that it was created on the Imbrium floor before the lavas started to flow? The floor of Cassini appears to be at sea level with the rest of Imbrium (this would not be possible if Cassini were created after the lava flows), and aside from a few obvious disturbances, much of it is quite smooth. Cassini’s size (35 mi.) and the width and complexity of its ramparts, suggest that its basin should have substantial depth and central mountain peaks, but it is quite shallow.

Cassini: [NE/E10] Can you tell by looking at Cassini that it was created on the Imbrium floor before the lavas started to flow? The floor of Cassini appears to be at sea level with the rest of Imbrium (this would not be possible if Cassini were created after the lava flows), and aside from a few obvious disturbances, much of it is quite smooth. Cassini’s size (35 mi.) and the width and complexity of its ramparts, suggest that its basin should have substantial depth and central mountain peaks, but it is quite shallow.

Take a close look at Cassini under high magnification. The two tiny bumps (you might see three) just to the southwest of the largest internal crater give you a clue about the timing of the impact. Cassini was at one time quite deep, with central mountains appropriate to its size. The post-Imbrium lavas that flooded the crater rose so high that all that is left of the once impressive central mountain peaks are these little bumps.

Take a close look at Cassini under high magnification. The two tiny bumps (you might see three) just to the southwest of the largest internal crater give you a clue about the timing of the impact. Cassini was at one time quite deep, with central mountains appropriate to its size. The post-Imbrium lavas that flooded the crater rose so high that all that is left of the once impressive central mountain peaks are these little bumps.

The floor of Cassini is covered with features, some of which can be easily seen with a small telescope, but others are quite delicate and require larger apertures and good seeing. Make a rough sketch of what you see and come back later to fill in more details. You will have no trouble with the two larger internal craters, Cassini A (9 mi.) and Cassini B (6 mi.). Can you see how Cassini A is shaped like a teardrop pointing toward the northeast? The teardrop shape was the result either of a closely spaced double impact or of an oblique impact.

Notice how Cassini’s glacis, a wreathlike outer rim that would normally extend out farther, has been partially covered by the flow of Imbrium lavas. Cassini and Archimedes (to its southwest, viewable Wednesday evening) share a similar history. Compare them closely to see what characteristics they share in common.

======================

It is highly recommended that you get a copy of Sky and Telescope’s Field Map of the Moon, the very finest Moon map available for use at the telescope. It is available for $10.95 at www.skyandtelescope.com and on Amazon. All features mentioned in this blog will be keyed to the grid on the Field Map and will look like this: Plato: [NW/D9]

Credits:

Courtesy of Gray Photography of Corpus Christi, Texas

Lunar photos: NASA / USGS / BMDO / LROC / ASU / DLR / LOLA / Moon Globe. Used by permission

- Rupes Cauchy: A Best Known Fault on the Moon - July 22, 2024

- Moon Crater Schickard – Crater Floor has Stripes - July 15, 2024

- Moon Craters Langrenus and Vandelinus - July 8, 2024